Further Artforms

Guangzhou nut carving

Guangzhou nut carving is a traditional folk craft that involves carving walnut shells or pits from other dense fruits, such as olives, peaches, apricots, and cherries, popularised during the Ming Dynasty. The carvers utilise the natural undulating forms of the shells and pits, and through engraving, carving, chiselling, and drilling, they create images and texts on the surfaces. The patterns are often symmetrical, heavily detailed, and with delicate and vivid images. The aim is to evoke a ‘ghost craftsmanship’ – essentially to avoid any marked traces of carving. Guangzhou was renowned for its olive-stone carving, with key artisans such as Chen Zuzhang and Zhan Gusheng, who were early adopters of the olive carving technique.

Olive carving utilises the material qualities of the black olive kernel, which is slowly and delicately carved to reveal subtle details, lines, and images. Since the 20th Century, over 50 various styles of olive carving have emerged, including multi-layer flower boats, carved crab cages, fishing boats, and chess pieces. Zhou Hanjun is one of the few remaining inheritors of olive-stone carving, maintaining the legacy of Guangzhou nut carving practices. With olive carving only accessible during the humid months of the year, and the rapid decline of black olive trees, the practice faces a worrying threat of erasure.

Zhou Hanjun, Carving an Olive-Stone in Zhuhai City in South China's Guangdong Province, May 31, 2019.

The Hakka Martial Arts Lion Dance

Pioneered by the Hakka people from Jiaying, Huizhou and Chaozhou, the Hakka Lion Dance emerged in Taiwan during the Qing Dynasty. The original intention of the Hakka dance was to ward off bandits and other threats to the Hakka people, before it was adopted into festival culture. Over the last two centuries, the Hakka Lion Dance has faced suppression, erasure, and neglect, with the practice only recently regaining its public status. The Hakka Lion’s (also known as the Box Lion) characteristic feature is its square mouth, which can open and close, featuring two rows of teeth and a cartoonish nose.

Hakka performances typically consist of three characters: the Spirit Lion, the Big Face, and the Little Face, accompanied by a musical ensemble that features gongs, drums, and cymbals. Since each dragon head is made by hand, the construction process is labour-intensive and time-consuming. Performing with the head also requires rigorous training, mainly due to the weight of the dragon head, the intricacy of the martial arts-style dances, and the complex character lore. Yet, due to long-term neglect and a specialised knowledge of both the artistry and the performances, the Hakka Lion Dance risks cultural erasure.

Hakka Lion Dance in performance

Paiwan Mouth-Nose Flute

One of the most significant crafts from the indigenous Taiwanese tribe, the Paiwan, the Mouth-Nose Flute is a dual-pipe bamboo instrument played using the breath from the nose. Its twin-pipe system allows one pipe (with finger holes) to create the melody, while the other sustains a continuous drone. Initially reserved for noble men and warriors, the Mouth-Nose Flute was extensively used in celebrations and festivals, particularly to honour newlywed couples and in the Ijemavelja ceremony. Due to the population decline of indigenous communities and the restrictive access to the instrument, the Paiwan Mouth-Nose Flute has fallen out of favour. Artists such as Pairang Pavaljung, Shao Niyao, and Gilegilau Pavalius are among a few remaining practitioners, recognised as national treasures by the Taiwanese government.

Shao Niyao, playing the nose-mouth flute

Kesi silk weaving and tapestry making

The earliest examples of Kesi silk weaving and tapestry date back to the Tang Dynasty, with the tapestries often used to protect scrolls and support paintings. However, it became a flourishing art form during the Song Dynasty, where the practice became used for clothing, courtly furnishing, and to copy paintings.

The term Kesi translates directly to ‘cut silk’, evocative of the way the weft threads are tucked into the textile, becoming invisible in the completed fabric. Light and delicate, Kesi tapestries are renowned for their detailed pictorial designs, often reflective on both sides of the tapestry. Unlike European brocade weaving, each colour area is woven from a separate spindle, making the process incredibly time-consuming and technically intricate. As such, this handmade art form has very few inheritors, earning its status on UNESCO’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2009. Huang Lan-ye is an artisan continuing the legacy of Kesi silk weaving, having founded the National Centre for Traditional Arts Taiwan, where she offers public courses in the practice.

Kesi Silk Tapestry Wrapper from “The Admonitions Scroll of Gu Kaihi”; Song Dynasty

Suzhou Song Brocade

Song Brocade began in the Song Dynasty, becoming one of the three main brocades in China (alongside Shu and Yun). Its primary production was in Suzhou, also known as the ancient ‘Silk City’. Unlike the Kesi silk weaving, Song Brocade interlaces vertical warp threads and horizontal weft threads to create intricate, colourful patterns. The bright fabrics of the Song Brocade were often used to decorate the frames of paintings and calligraphy, as well as for personal furnishings and noble clothing. Alongside the visual appeal of the brocade, the texture of the silk weaving makes Song Brocade one of China’s classic craft beauties.

Song Brocade is woven using a special loom with two gold threads (one on the front and the other on the reverse) to carefully interweave the weft and warp threads. Ms Xiaoping Qian is the national inheritor of the Song Brocade craft, describing the art as ‘one of the noblest and complicated arts.’ Both restoring original Song Brocade textiles (such as the double-lion brocade in 2003), as well as crafting new, original pieces, Xiaoping Qian is keeping the skill alive in contemporary culture.

Ms Xiaoping Qian working on a Song Brocade loom at her studio.

Suzhou Lanterns

With over 1,500 years of history, Suzhou lanterns are one of China’s oldest art forms. Modelled after traditional Chinese pavilions, towers, and terraces, Suzhou lanterns are meticulously decorated objects that reflect the Suzhou landscape and wildlife. These lanterns are usually displayed during the Lantern Festival, which marks the end of the Chinese New Year celebrations. The construction of these lanterns requires detailed pre-planning and production efforts, involving the creation of the skeleton frame, cutting the copper-paper panels, pasting each panel together, carving details into the frame, and painting the designs onto each panel.

National representative inheritor, Wang Xiaowen, has preserved the artistry of the Suzhou lantern, notably through his restoration of the ‘Ten Thousand Eyes Luo Lantern’. With only second-hand descriptions and aged historical materials, Wang Xiaowen and Wang Liqui undertook the monumental task of restoring the lantern to its former glory – a 6-foot-tall lantern with almost 24,000 eyelets. Such work helps conserve traditional Chinese arts whilst also ensuring that modern-day audiences can experience these masterpieces.

Wang Xiaowen working on a lantern with his daughter, Wang Liqui

Shan Making

Shan (‘fan’) production has a long history in Hangzhou, dating back to the Song Dynasty and was frequently used to pay tribute to the Qing Imperial Court. Carved, inlayed or painted, these fans are diverse and delicately designed. The Wangxingji brand has established a monopoly over Shan production in Hangzhou, with its factory known for its distinctive quality and diverse range of fan designs. These include black paper fans, known for their ‘Three Stars’ motif; white paper fans; Sandalwood fans, the most common and appealing; and speciality fans, often used for operas, dances, and as gifts.

The Wangxingji brand is also celebrated for inventing the la hua technique – a method that involved carving patterns onto the fans using thin steel wires. The fan’s ribs are constructed from materials such as bamboo, ebony, ivory, sandalwood, or bone, resulting in a low production rate due to the rarity and illegality of these materials. Yet, to keep the practice alive, the Wangxingji company has employed and recognised the skill of numerous Masters of Arts and Crafts within Hangzhou, as well as avoiding an over-reliance on mass technical production.

Master Sun Yaqing, Design for Lotus Rhyme, 2022, Hangzhou

Woodblock printing

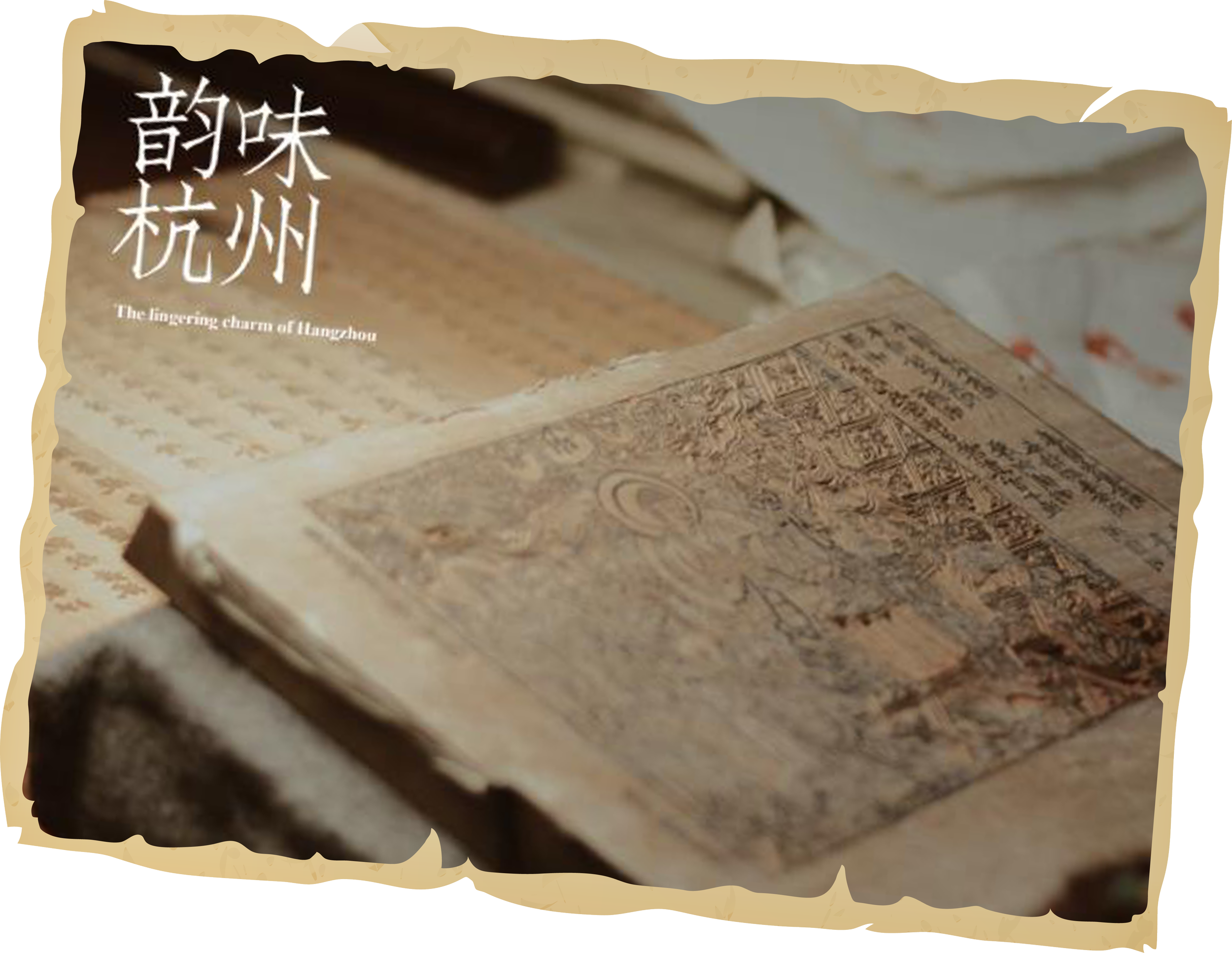

Spanning over 1000 years, woodblock printing is a staple of Chinese craftsmanship. During the Northern and Southern Song Dynasties, Hangzhou was renowned for its advanced woodblock printing, recognised for both its high production volume and exceptional quality. The process consists of four stages. The first is carving the block – artists carve specific texts or images into the reverse of a wooden block, to create a relief. Then, the block is brushed with ink, and a sheet of paper is placed over it, lightly rubbed with a pad to transfer the design. What remains after the drying process is a detailed, precise design that can be used in manuscripts, as art, or for calligraphy. Carving the wood block is a skilled and arduous task, but each block can produce an unlimited number of impressions. The technique was recognised as part of UNESCO’s National Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2011.

Traditional Hangzhou woodblock carving

Puhui New Year Pictures

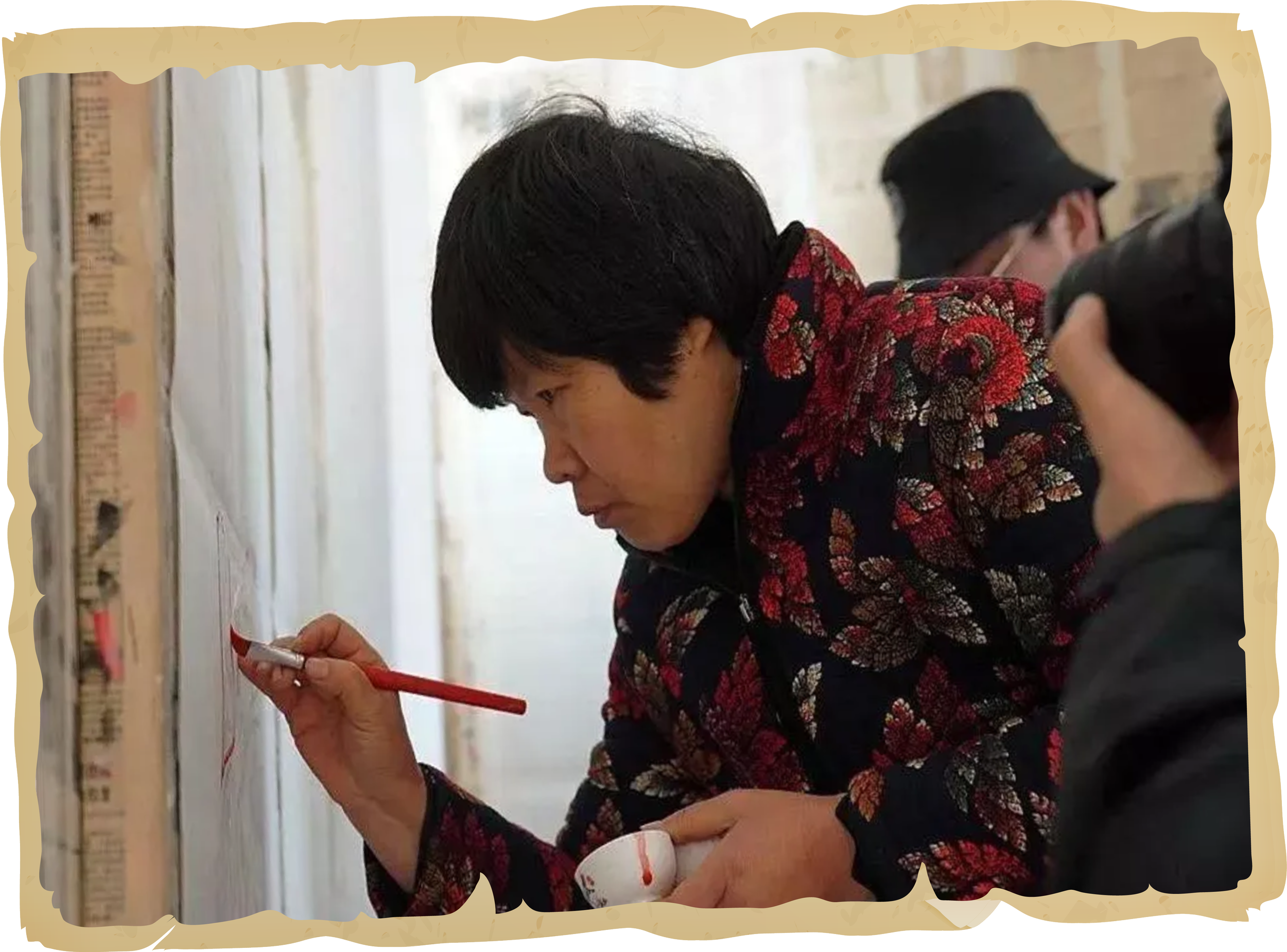

The Puhui New Year Painting (also known as Grey or ‘Flapping-Ash’ New Year Painting) is an ancient Chinese painterly style that first emerged during the Chenghua period of the Ming Dynasty. This particular type of New Year painting is only sourced in Gaomi, Shandong Province. The practice originated as a means of copying traditional temple murals and selling them in local markets, but it soon evolved into its own distinct art form. The Puhui style uses willow twigs burned to charcoal to draw the outlines of the paintings. Since charcoal smudges easily, artists need to keep their lines narrow and retrace them several times to achieve crisp lines. These resulting prints are then hand-painted. Since these prints correspond with the Lunar New Year, their motifs often reflect joyous celebrations and imagery, including babies (symbolising prosperity), operas, fairy tales, and Chinese landscapes.

Native Gaomi resident Wang Shuhua is a fifth-generation inheritor of the Puhui painting practice. As part of the effort to preserve and develop the practice, the Gaomi City Tree Flower New Year Painting Art Museum and the Inheritance and Education Interactive Area of the Gaomi New Year Painting have been established. These spaces provide teaching, apprenticeships, and studio sessions to encourage residents to engage with traditional Chinese folk art.

Wang Shuhua demonstrating Puhui New Year Painting to her students, Gaomi

Gaomi Clay Sculptures

Originating from the Niejiazhung Village, Gaomi clay sculpting is a 400-year-old folk tradition known for its vibrant and sound-making figurines. Initially intended to serve as containers for fireworks, these small figurines quickly became a favoured market-stall craft. Lions, tigers, and beasts from Chinese folklore are the most common themes in Gaomi clay sculpting, predominantly taking from the Sun Wukong and Eight Immortals mythologies. Painted in bright, vibrant colours, these figurines function as symbols of good fortune and protection from evil spirits.

Many of these sculptures are also designed to produce specific sounds, such as the roar of the lion sculptures. Nie Peng, following in the footsteps of his father Nie Chenxi, continues the legacy of the Gaomi clay sculpture. In 2020, the pair created large-scale figurines that helped support China’s fight against the Coronavirus and to thank medical workers on the frontlines. Nie Peng stated that these colourful and playful creatures were designed to ‘pay homage and help spread awareness of the importance of epidemic prevention and control.’

Nie Peng and Nie Chenxi, Coronavirus Prevention Gaomi Clay Sculptures, 2020.